The Art of Science and the Science of Art

I thought a lot about the relationship between science and art when my coworker, Ammie Martin, sent me a link to the article, “The Animation Lab at the University of Utah brings Molecules to Life” by Jonathan Feakins, which had been published in Chemical & Engineering News. The article featured Dr. Janet Iwasa, a Biological Animator at the University of Utah. Iwasa became interested in the art of animation while earning her Ph.D. in cell biology at the University of California, San Francisco. After watching an animation during a scientific presentation, she wondered how her own research might benefit from a visual component, and decided to take art classes to learn animation at a neighboring school.

Today, Iwasa’s lab at the University of Utah trains postdocs in the skills required to transform scientific discoveries and hypotheses into animated visual art. The article notes that an important aspect of her work is that it can “serve as a stress test to a researcher’s current hypothesis.” During a project Iwasa worked on to animate a type IV pilus structure, which required her to “concoct a protein cage above and within the inner membrane of the bacterial cell surface,” she noticed a problem – “the proteins didn’t fit.” Iwasa brought the issue to the attention of the researchers who now knew they now had to re-evaluate the data set and adjust the hypothesis, which they did, successfully.

Ammie had sent me the article because she knew I would enjoy the art aspect. In addition to working as a Senior Technical Editor at Environmental Standards, I am also an artist (I paint as Paula Kay). I found it notable that the animators stumbled upon the apparent flaw in the hypothesis, and the flaw was only discovered as a result of creating that visual rendering. In this example, it is clear that the art process really supported the progress of the science.

It’s funny because so many people think that if someone has a mind that understands science, they cannot also be artistic, but that’s not true. I am both, and being both makes perfect sense to me. I use scientific thinking when I am creating art – when I am selecting and mixing colors, when I am figuring out the best strategy for creating a realistic portrayal of a three-dimensional thing on a two-dimensional surface, figuring out where to put light and shadow, deciding which brush or application tool will be best to achieve a certain outcome, etc.

I absolutely need to understand the properties of light and be able to figure out how to apply them to a painting. I need to assess all the data about my subject image in order to create a realistic depiction – hue variations, size transitions as subjects move further into the distance, etc. In both science and art, attention to detail is critical.

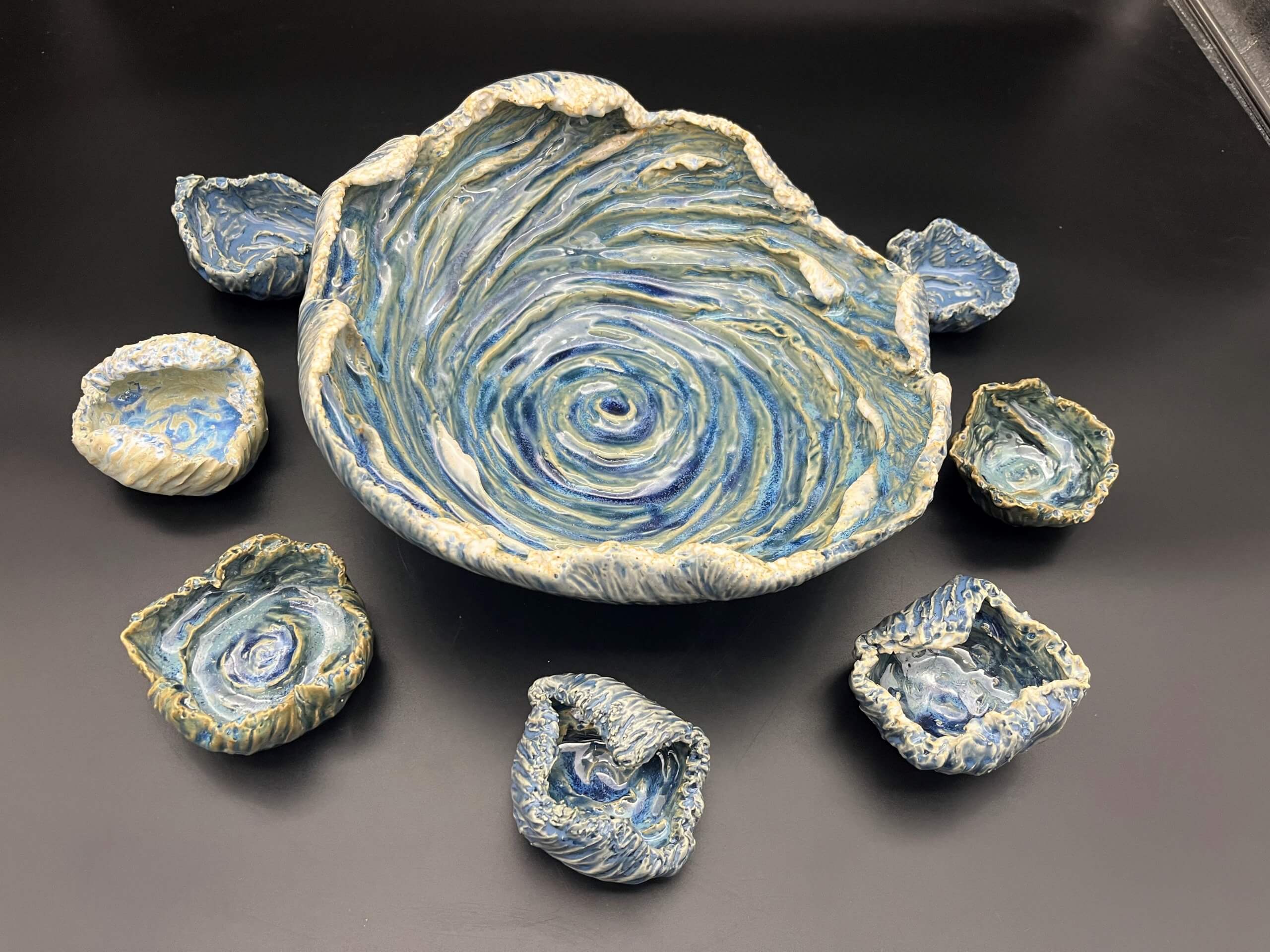

Another coworker, Meg Michell, Senior Associate Chemist, is a ceramicist in her spare time. She had taken her first ceramics class in the 1990s, but after her kids started college, she began doing ceramics on a regular basis. I asked her what she thought about the idea some have that scientists can’t be artists and vice versa. She replied, “I think some people might think that way, but many scientists and artists know better.”

Meg is inspired by nature and enjoys making organic shapes that might remind someone of something they have seen in nature like a seed pod or deep ocean creature, even if they are not quite sure what it is. “I think there are a lot of benefits to thinking ‘outside of the box’ in both science and art, and creativity is not limited to the art world as both involve experimentation.

“Glazing is all chemistry!” exclaimed Meg. When glazing ceramic pieces, there are so many components that will impact how the glaze will come out that only start with its composition. While some glazes are like paint in that the color you apply is the color that you get, most are not. Reducing/oxidizing environments, firing temperature and duration, cooling time and environment, reactions with other glazes, and weather can all impact how the glaze turns out. For example, glazes containing copper oxides can be various colors depending on if you are firing in an oxidizing (green hues) or reducing (copper red) environment – pure chemistry. And the best way to determine how a glaze will come out is through experimentation.

Meg added, “Most people like to have some sort of creative outlet – from traditional art forms to woodworking, gardening, cooking, creating music, etc., and artists often must have a grasp of the scientific principles that their medium requires,” said Meg. “One person I went to graduate school with was studying chemistry to pursue art restoration, which involves understanding the chemistry of various artistic mediums throughout history and how to use them.”

Science and art are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they work together quite nicely.